Five duties of a technical writer

Writing requires that you try to reach your reader. Technical writing doubly so. And that’s the part that isn’t easy. There are obstacles, and you have to do the work of overcoming all of them all of the time.

Here are five of my rules for technical writers.

-

You have to understand your topic.

In a lot of life, in conversations and in writing, you can have a vague idea of how something works. (For example, you can put gasoline in a car without understanding how the gas fuels an engine.) That’s not true in technical writing. You cannot explain what you do not understand. You have to know exactly what the ideas are, and what all the words mean. Although you don’t have time to become a subject matter expert in everything you write about, you must invest the time and brain-strain to become a student of the subject. And you must resist the seductive pleadings from non-writers to just clean up the writing of someone who does understand the topic. You’re not there to give a polish to writing that you do not understand. You’re there to explain. You have to take that commitment seriously.

-

You have to understand your readers.

How much context do your readers have? You have to know before you start to write. Some readers need a thorough explanation of the concepts before you explain how to complete a task. (For example, if a user wants to back up her laptop data, just what a “cloud backup” refers to and how that works.) Some readers are turned off by too much explanation, and just need a refresher. (For example, the user’s options are a backup to a local device, either via cable or over the wireless network, or to a network device. And the reader may not need those options explained any more than that.) Or they need an expert tour guide who remembers to shut up frequently enough to allow them time to explore the terrain. You have to serve all your readers, and resist the lie from the lazy that there is only one type of reader. Before you even begin to consider the context of your readers, you have to begin by realizing that your context is not their context.

-

You have to have humility and empathy.

You are not the most important person in this communication; the reader is. If you do not understand in your core that you are there to serve the readers, then it is frighteningly easy to allow your greater knowledge to flavour your thinking (or worse!—your actual writing) with unconscious condescension. But you are not doing your readers a favour by telling them what they do not know. They are doing you the favour of giving you their time and attention. You must respect the reader and respect how they are feeling when they look for help completing a task. (Hint: Have you considered the probability that the reader is under stress because something has gone wrong with the task before them?)

-

You have to read what you wrote.

You have to read what you wrote critically so that you can make it better: easier to understand, more relevant to the reader, easier to skim, and many other things. As you read, you have to keep in mind the reader, which is why items 2 and 3 have to be completed first. “Dash it off, send it off” is not how technical writers operate.

-

You have to rewrite what you write.

Writing is re-writing. There is a 0% probability that you wrote everything perfectly the first time. You can save yourself and your co-workers time and effort by rewriting before anyone else ever sees it. In the event that you are fortunate enough to have someone else review your work, you have to take their comments seriously in light of what is best for the reader. Technical writing is no place for a writer to have an ego about someone suggesting a change to their phrasing.

I will not soon forget the subject matter expert who responded to my request for an explanation of a feature (and its intended use) by writing a long document for me to read. It was a document that could be understood only by someone with advanced experience in his position. I know; I asked junior people in that field to read it, and they could not grasp it. I scheduled a meeting with the expert to clarify the points that confused me. My goal was to explain the feature to the user.

The meeting ended with the expert absolutely irate that I would not just copy and paste what he had written into the user documentation. “Why can’t you just use what I wrote?” he fumed.

His frustration was real and should not be overlooked, downplayed, or worst of all, belittled:

- He could not understand the difference between writing for himself and his peers and writing for a user. He was not stupid; he just could not grasp the idea, let alone why it was important. He had no empathy for the user.

- He had spent a long time writing his document, and had become invested in the way he had written his explanation. He had little experience in writing, less experience in revising what he had written, and no experience whatsoever in writing for the user.

I was fortunate enough that I understood this expert’s natural pushback against people who want to “improve” something by adding their individual contribution, not all of which “improvement” is helpful.

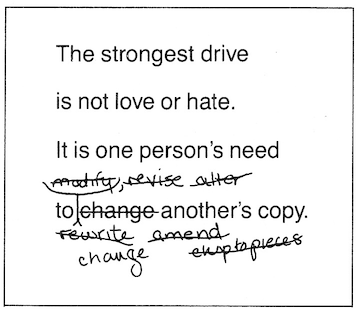

[Text illustration as reproduced in The Elements of Editing by Arthur Plotnik (1982)]

You likely have had the experience of reading a journalist assigned to a news story about some aspect of science that oversimplified the science, or misrepresented the results of some scientific research. And if you have had that experience, you may also recall an occasion on which the person who wrote the story’s headline (usually not the person who wrote the story) and thereby oversimplified or mispresented the message still more.

So the fear of non-experts has a place. But as a technical writer, you have expertise, too. You have expertise in communication that bridges the gap between all the knowledge that an expert has and the information that the user needs to complete the task.

As you progress through your career as a technical writer, you will encounter more people who are not experts in communicating, and have not considered the possibility that anyone can have expertise in communicating. You can show other experts that you respect their expertise and that your expectation that they respect your expertise is a reasonable request.

Another time, we’ll talk about this idea that anyone can write.